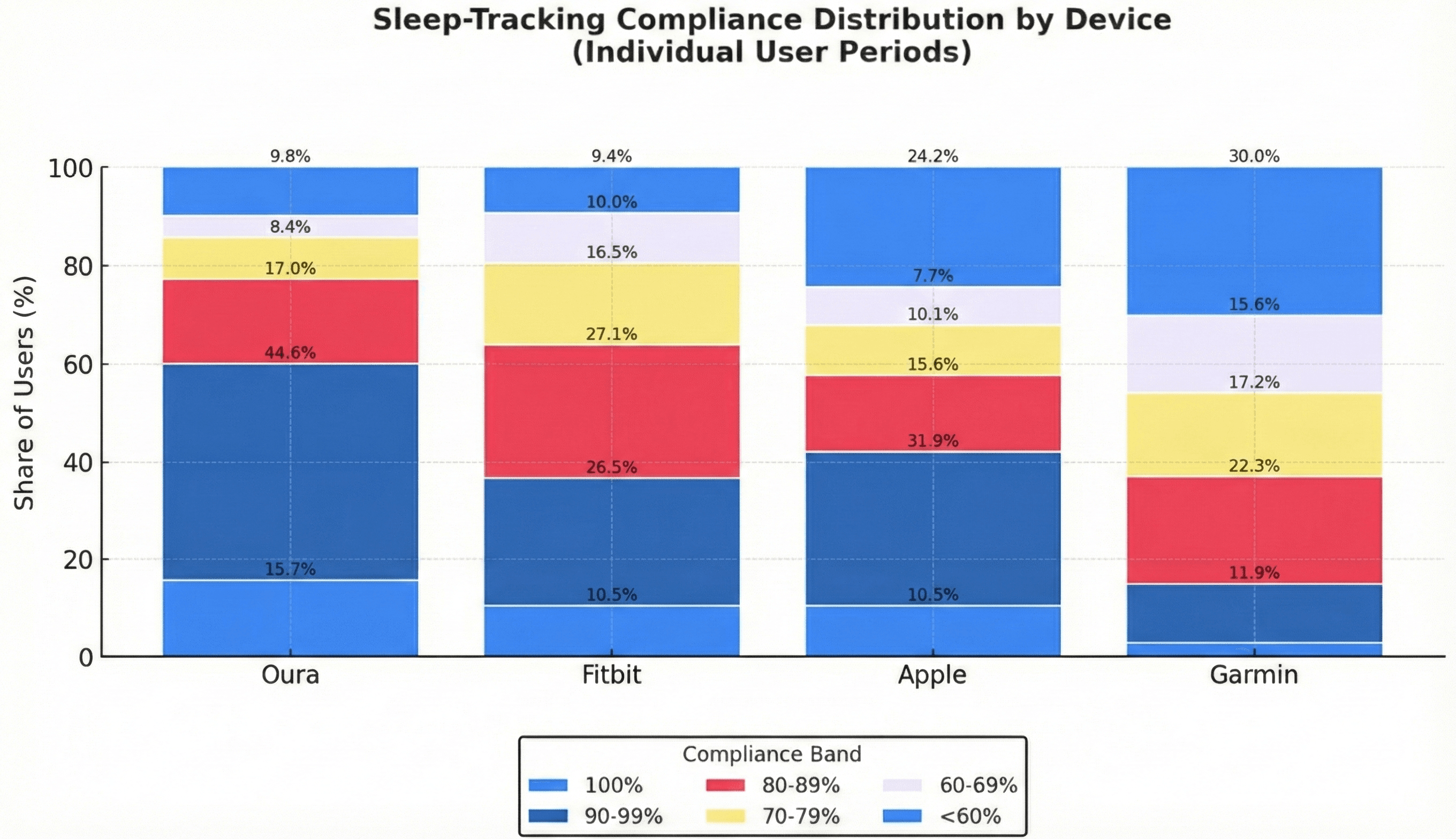

- Wearable sleep compliance is high in real-world settings, with Oura and Fitbit users in particular showing rates that meet or exceed those seen in structured clinical studies.

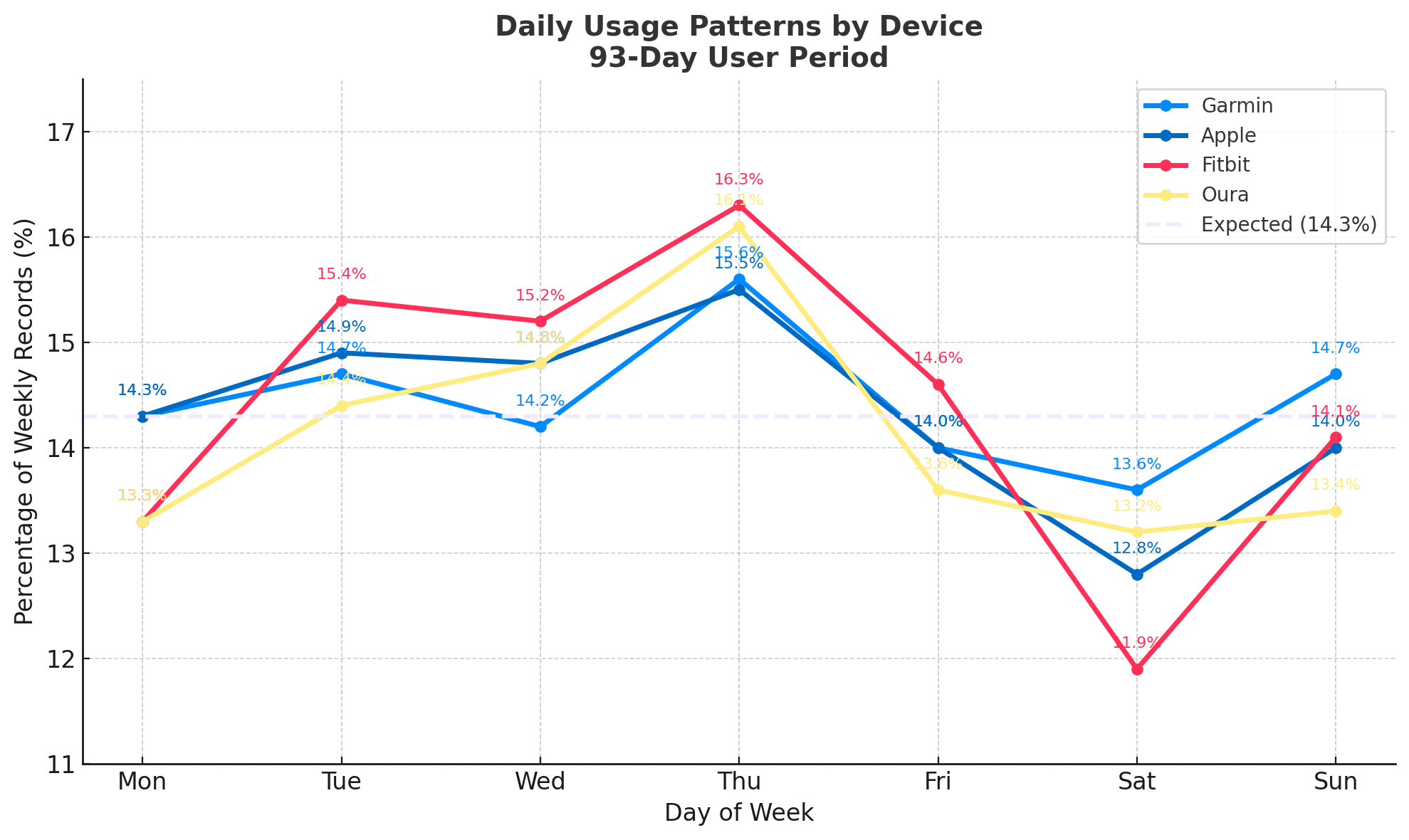

- Weekly usage patterns are consistent across devices, with Thursday the strongest night and Saturday the weakest, highlighting subtle but predictable rhythms in user behaviour.

- These devices are not only accurate but also reliably used, making them powerful tools for sleep and recovery research outside the lab.

Sleep Tracking

How Do People Really Use Wearables?

By Alistair Brownlee and Cameron Crawford

December 9, 2025

How Do People Use Their Wearables?

At Terra Research, we care not just about measurement accuracy, but also about how people interact with their devices over time. That real-world usage determines the quality and consistency of data we can rely on — critical for meaningful sleep and recovery research. It’s also useful information for our terra customers. Building a product based on daily recovery and sleep data? Encouraging the use of a particular wearable device might provide more consistent data.

This analysis focuses entirely on sleep (overnight) data, asking a simple but essential question: how often do users actually log sleep data? I used data from four wearables (Oura, Fitbit, Apple, and Garmin) over 93 days, from 1 May to 1 August 2025. I only examined compliance between the first day of device use and the final day of the period. This was important because many users were onboarding during May and June, particularly those using Fitbit.

Weekly Usage Patterns

It’s not just about how often users log sleep, but also which nights they choose to wear (or not wear) their device. Across all platforms, Thursday shows the highest usage, while Saturday is consistently the lowest. Fitbit users exhibit the greatest fluctuation, whereas Garmin users remain comparatively steady throughout the week. These differences are statistically significant but small, so I don’t think they will have much impact on research. I actually found it surprising how similar the usage profiles are across the four wearables — and it’s a little amusing (though not especially important) that Fitbit users clearly stand out on the chart below for choosing Saturday as their “wearable night off”!

How Wearable Compliance Stacks Up in Clinical Studies

Compliance is a constant challenge for any researcher asking participants in a study to use wearables. Perhaps users who choose to adopt wearables in their own lives show better compliance, and we can learn lessons that help in a research setting. I looked into adherence data from the literature to understand how this compares to traditional clinical studies:

A scoping review examining wearable use in cancer patients, with a focus on sleep and activity, found adherence rates ranging from 60% to 100%, with the highest rates typically observed in 12-week studies.

Another study, tracking in-the-wild Oura usage for a month, reported that 24 out of 31 participants maintained usage above 80%.

Broader clinical applications of wearables show patient adherence typically between 70% and 80%, especially when integrated thoughtfully into trials.

Placed alongside our data, wearable sleep compliance rates — particularly for Oura and Fitbit — meet or exceed those seen in structured clinical contexts. That’s noteworthy, given that compliance in clinical studies is often externally motivated. To me, it demonstrates the benefits of “in-the-wild” wearable research and the potential value in recruiting participants who are already avid users.

Why This Matters

Finally, the key insight is this: wearable devices support genuinely high sleep-tracking adherence, even under unmonitored, real-world conditions. A substantial share of users log data nearly every night. The device-specific weekly rhythms (such as Saturday dips) are interesting to recognize, and they might even influence the design and analysis of longitudinal sleep research.

Compared with structured clinical trials, real-world wearable usage rates are not only comparable but in some cases superior. In other words, these devices are not just accurate tools — they are also reliably used. That combination is what makes them powerful for real-world sleep and recovery research.