We tested whether the menstrual cycle leaves a detectable signal in wearable sleep data — analyzing ~3 million nights of sleep, using autocorrelation to separate biological rhythms across genders.

Luteal phase recovery metrics look worse, but the body isn't broken — women show higher heart rate (+0.2 std), lower HRV, and more fragmented sleep, driven by progesterone's shift in autonomic balance.

Key takeaway — your body can still perform the same in both the luteal and follicular phases, but a lower readiness score in the luteal phase just means your recovery is more costly.

Women's Health

Why Readiness Scores Misread Women's Capacity

By Alistair Brownlee, Rocio Mexia Diaz and Halvard Ramstad

January 29, 2026

What Does Night Temperature Tell Us?

Every night, our bodies quietly tell a story. As we sleep, core temperature lowers, heart rate slows, breathing steadies, and the nervous system resets [1].

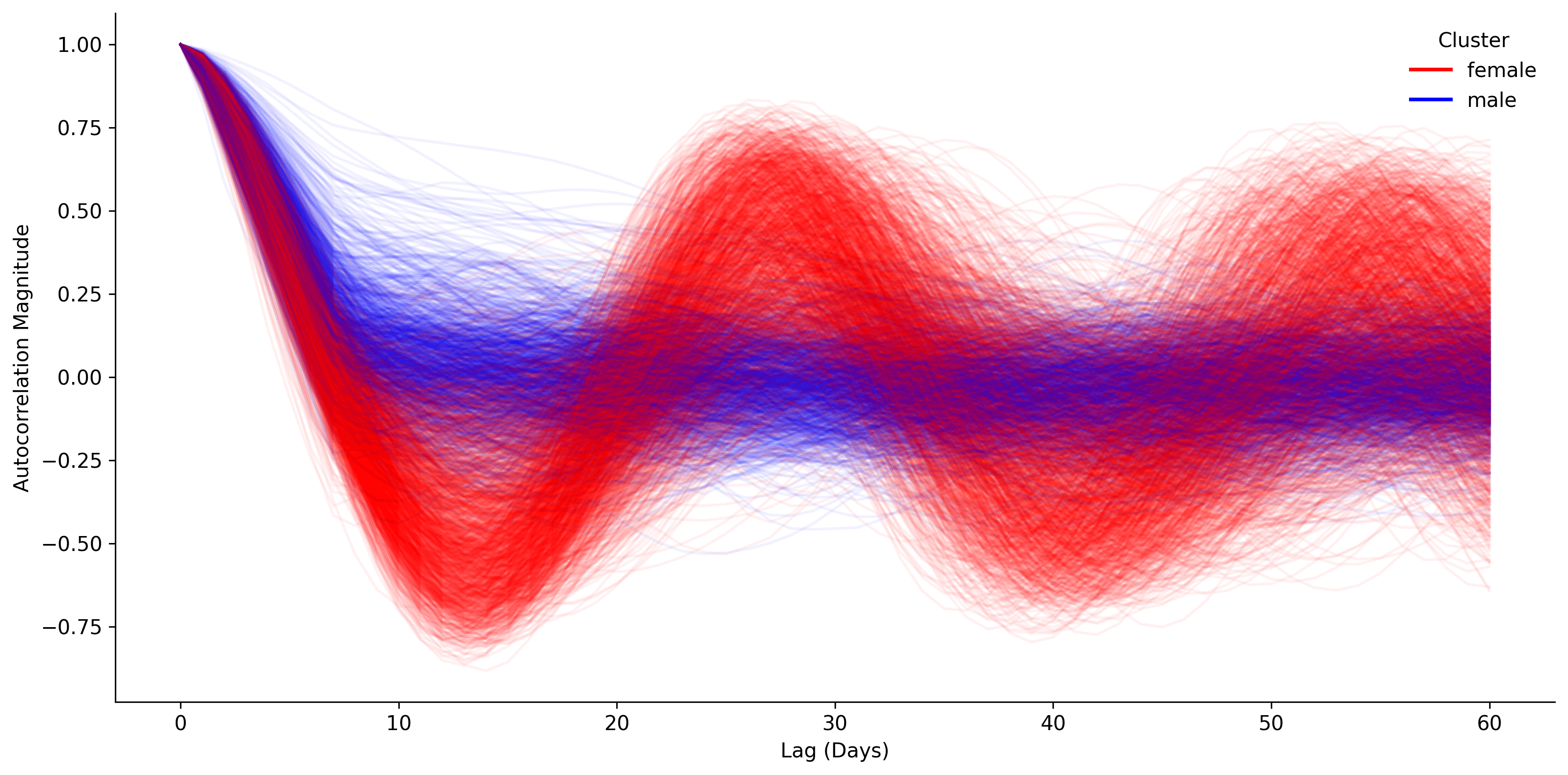

These patterns follow rhythms - daily, weekly, seasonal - and are shaped by our routines, environment and biology. Today, we uncover a hidden rhythm: the menstrual cycle.The autocorrelation of our temperature signal tells us how well it aligns with itself when shifted in time, meaning we can expect peaks at all of the different rhythm time-scales.

The menstrual cycle is strongly tied with body temperature, and has a very distinct monthly pattern appearing in this autocorrelation profile as peaks roughly every 30 days. Using this, we can distinguish biological sex in our data and understand the effects of the menstrual cycle on sleep, physiology and behavior.

The Data

We looked at a cohort of 3,972 Oura users with a total of 2,964,571 nightly sleep records. To ensure stability in analysing long-term patterns, only sleep records from users with over 6 months of data and 80% data coverage were included.

Only the longest sleep records per night were retained to exclude naps and implausible recordings. The remaining cohort consisted of 906,572 records from 2954 users.Females in the cohort were identified as those with a more prominent autocorrelation magnitude within the 25 to 35 day window compared to the autocorrelation around 7 days.

This clustering assumes the dominating rhythm in females is monthly whereas in males its weekly. The resulting split was 1072 males to 1882 females.

The Luteal and Follicular Phases

The menstrual cycle is composed of four distinct phases: menstrual, follicular, ovulation and luteal. The menstrual phase exists within the start of the follicular phase and the ovulation can be defined as the transition from the follicular to the luteal phase. Therefore for simplicity, we assessed the differences between the two largest phases: luteal and follicular.

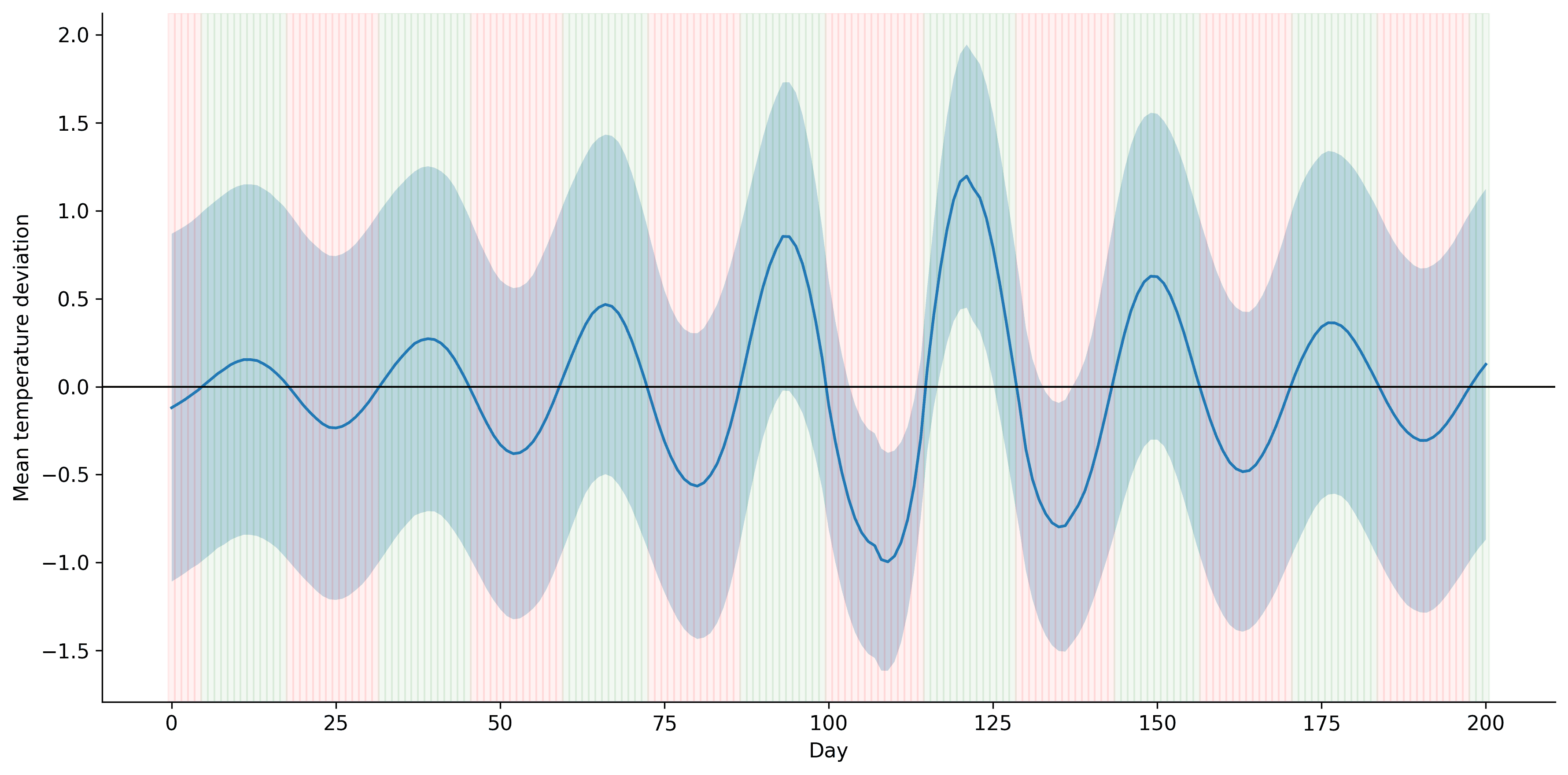

Our core temperature at night rises above our baseline temperature during the luteal phase and drops during the follicular phase[2].

Sleep and Physiological Differences in Women

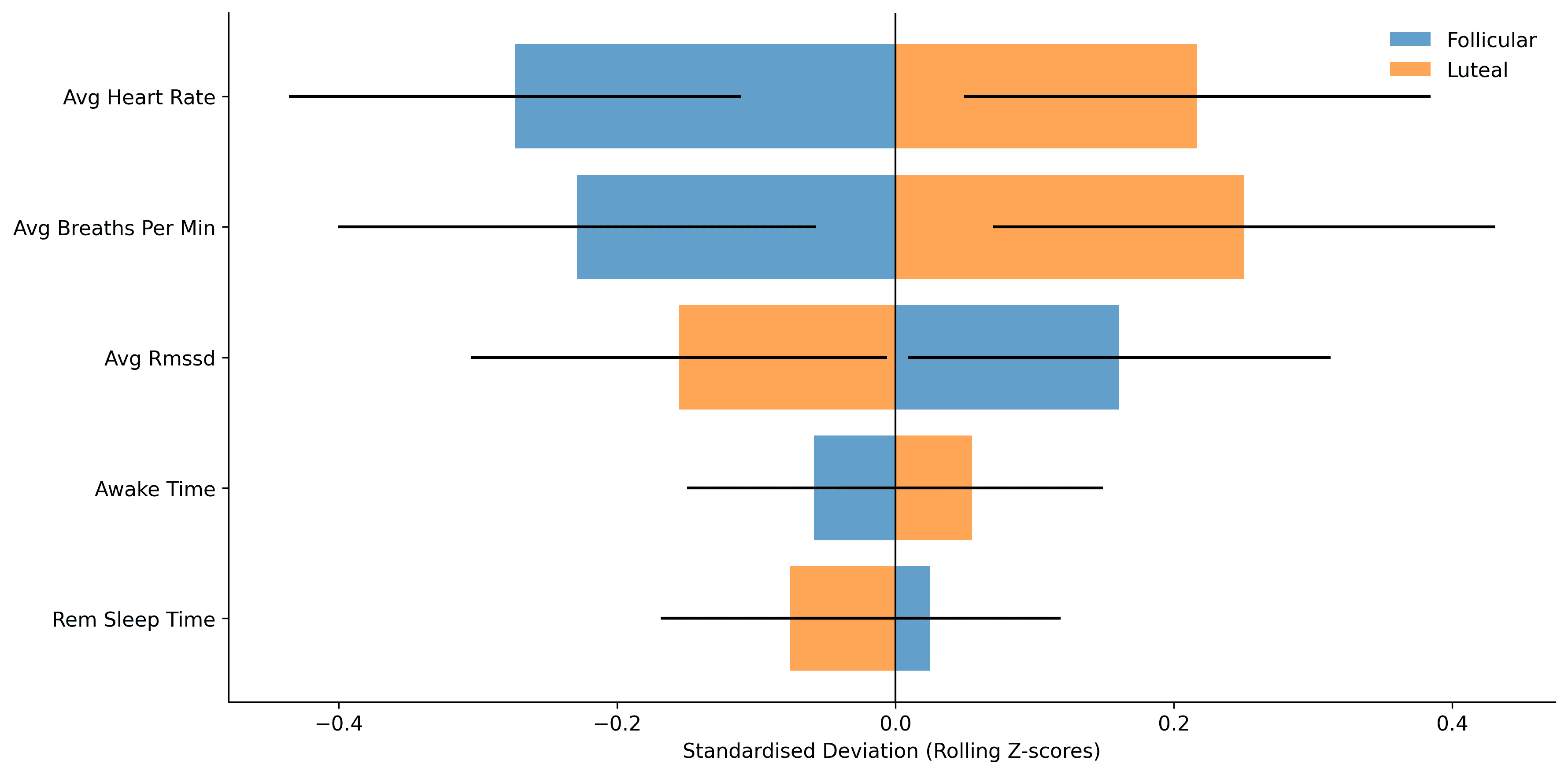

Feeling more tired and less recovered during certain weeks of the month is not just perception, it is measurable physiology. We compared rolling z-scores of sleeping metrics across the two phases to factor in inter-subject variability and moving trends over time.

Across the female population, the luteal phase is associated with:

- Higher nighttime heart and breathing rates

- Lower heart rate variability (HRV)

- Lighter, more fragmented sleep

These changes reflect the shift in autonomic balance across the menstrual cycle, where higher progesterone levels in the luteal phase are associated with increased resting metabolic rate, reduced vagal (parasympathetic) activity, and a state of greater strain and lower recovery potential. [3]

Performance: Recovery or Metabolism?

Motivated to understand how the physiological differences impact activity, we analyzed data from 50 users who had both Oura and another platform connected. Among 20 runners with sessions recorded in both menstrual phases, energy expenditure, total calories burned, and activity duration were all higher in the follicular phase.

Calorie and energy consumption metrics provided by the devices are primarily derived from distance and duration, and only moderately influenced by heart rate, making them an inaccurate gauge of metabolism. Mixed-effects modeling revealed that distance is a strong positive predictor of heart rate, as expected. Once workload was accounted for, there was no clear evidence that heart rate differs between the different phases, indicating comparable metabolic performance.

However, the fragmented sleep and lower HRV suggest that reduced activity in the luteal phase is more likely constrained by recovery capacity than by metabolic performance.

Why Does This Matter?

The menstrual cycle leaves a clear and measurable signal in night physiology. Far from being background noise, this monthly rhythm shapes sleep quality, autonomic balance, and how the body tolerates stress and training.

The luteal phase is a period of higher internal load: elevated heart and breathing rates, reduced HRV, and a more fragmented sleep all point toward a lower recovery capacity. This challenges our interpretation of readiness, performance, and sleep metrics. A given lower HRV value or restless night does not carry the same meaning every week of the month.

Accounting for menstrual phase adds context, helping distinguish between meaningful strain and normal cyclical variation, and aligns expectations for training and recovery.

References

[1] Alzueta, Elisabet, and Fiona C. Baker. “The Menstrual Cycle and Sleep.” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 18, no. 4, 2023, pp. 399–413, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38501513/.

[2] Zhang, Simeng, et al. “Changes in Sleeping Energy Metabolism and Thermoregulation During Menstrual Cycle.” Physiological Reports, vol. 8, no. 2, 2020, article e14353, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31981319/.

[3] Schmalenberger, Katja M., et al. “Menstrual Cycle Changes in Vagally-Mediated Heart Rate Variability are Associated with Progesterone: Evidence from Two Within-Person Studies.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 9, no. 3, 2020, article 617, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32106458/.