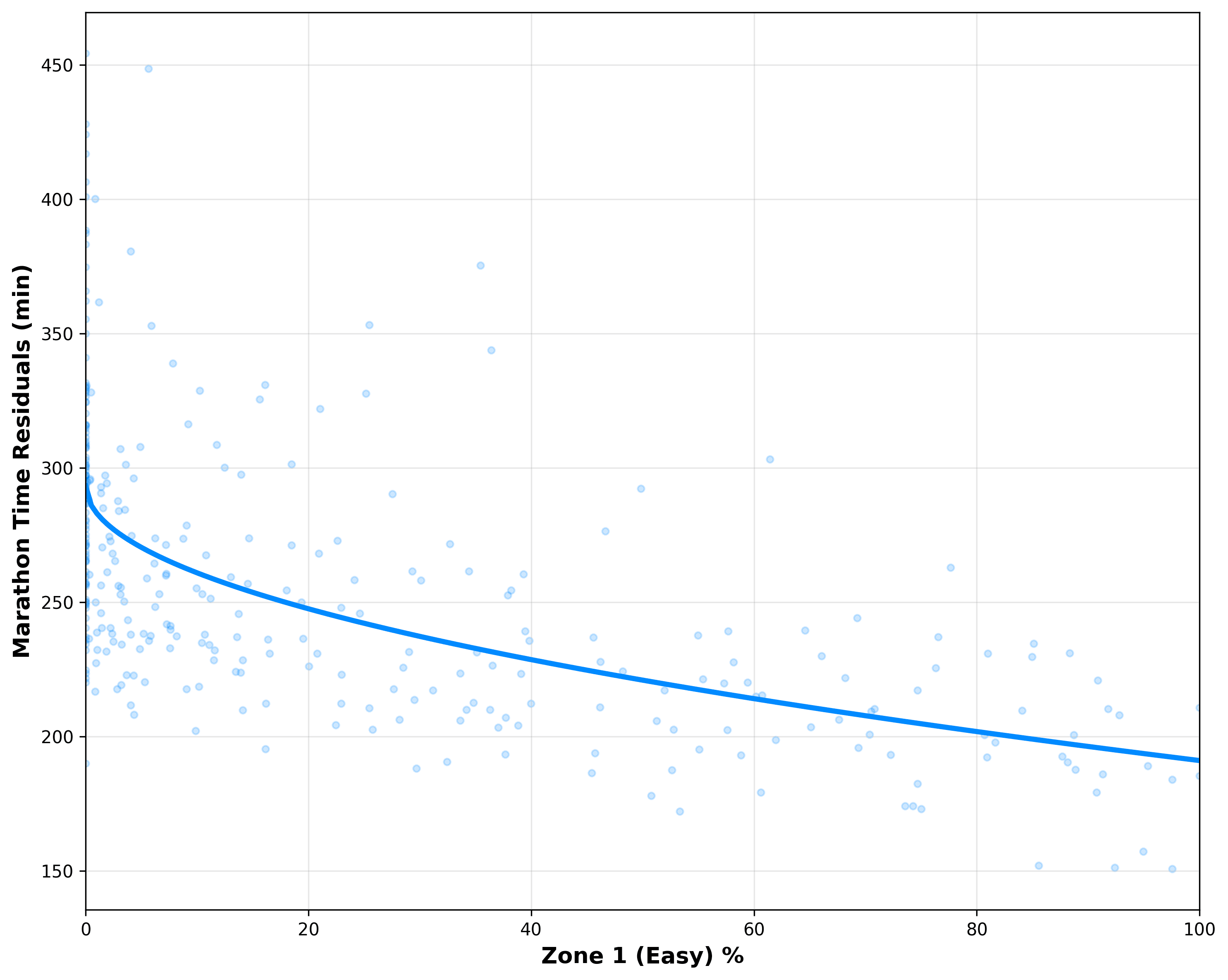

Easy running is still the dominant lever — as lower zone training takes up more of your week, the benefits tend to build faster rather than linearly, so each step toward more easy running often pays off more than the last.

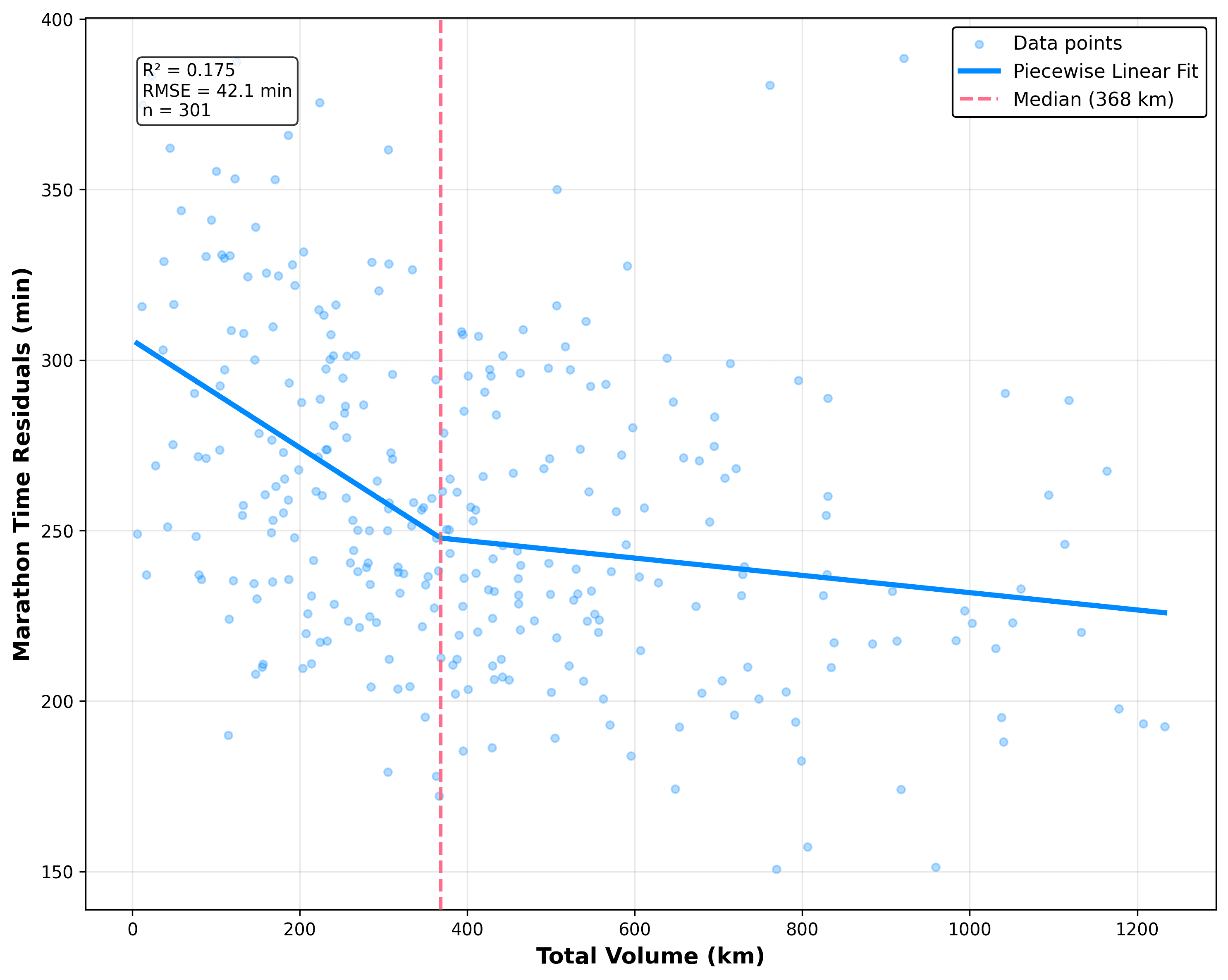

Volume has diminishing returns — total mileage helps up to roughly ~520 km per training block, but beyond that breakpoint the gains flatten and additional volume delivers much smaller improvements.

A more accurate, non-linear performance model — we move beyond last week’s linear assumptions and use a non-linear approach to fit marathon outcomes more closely, capturing how baseline pace, frequency, volume, and intensity split interact.

Marathon Training

How To Train For Your Next Marathon

By Alistair Brownlee and Halvard Ramstad

February 12, 2026

Non-Linear Modeling Marathon Pace

I think we intuitively know that human physiology is neither linear nor entirely predictable. Very early in my career, I remember thinking that the only upside of returning from enforced rest after an injury was the speed (read rate!) at which my fitness improved afterwards. In normal training, you don’t get better day to day; after a period of enforced rest, I felt better every session. Improvements in “Form” also seemed to happen in jumps. I’d train for months with no noticeable improvement, and then, all of a sudden, wake up as a different athlete. This all points to the fact that modelling human performance is inherently difficult, and, of course, there are many factors we don’t even know about.

If you tuned into our previous exploration of marathon performance through the lens of linear analysis, you'll remember the simple takeaways that emerged. We uncovered a world where greater training volume reliably translated into faster finish times, with each additional kilometre improving marathon time in a predictable manner. On the flip side, ramping up intensity tended to backfire, correlating with slower race outcomes. It was a broad-strokes approach, averaged across a diverse cohort of runners, with a simple conclusion: prioritise those steady miles, ease off the throttle on high-effort days, and watch the progress unfold.

As satisfying as those linear insights were, they are inherently limited. By smoothing everything into a single slope, linear models treated every runner as an interchangeable data point on a grand average line. They, of course, don’t capture the individual variation: the low-volume enthusiast who surges ahead with targeted intensity, or the high-miler whose endless loops yield only marginal returns because their easy days are too few.

That's where we pivot today, delving deeper into the terrain of non-linear modelling. Here, we're not just averaging trends; we're trying to honour the unique physiological narratives of each athlete, segmenting the data to reveal accelerating benefits, sudden breakpoints, and synergistic interactions.

Drawing from the same rich dataset as last week's blog (6 months of activity data on 425 runners in the lead up to a major marathon in 2025), we’ve experimented with techniques like piecewise linear regressions, square root transformations, and multifaceted interactions. What unfolds is a more detailed picture: why volume's promise tapers, how easy training's rewards compound, and the ways your weekly run frequency or innate speed can warp the entire equation.

The best fit for the volume-improvement relationship was a piecewise linear model, with the population median as the breakpoint at 523 kilometers. For those building at low volumes (≤523 km), the coefficient is +0.0081 minutes per kilometre, meaning 100 kilometers of training could reduce your time by around 12.8 minutes. Cross that threshold into high-volume territory (>523 km), and the landscape flattens: -0.0057 minutes per kilometers translates to a more modest 0.57 minutes saved per 100 kilometers, or about 3.2 minutes total.

Easy training exhibits accelerating, non-linear benefits: each additional percentage point of Zone 1 work delivers progressively larger performance gains as the proportion increases. This square-root-like pattern indicates that moving from 40% to 60% is typically easier and yields a larger improvement than moving from 0% to 20%, and that pushing toward 70–90% continues to yield meaningful returns.

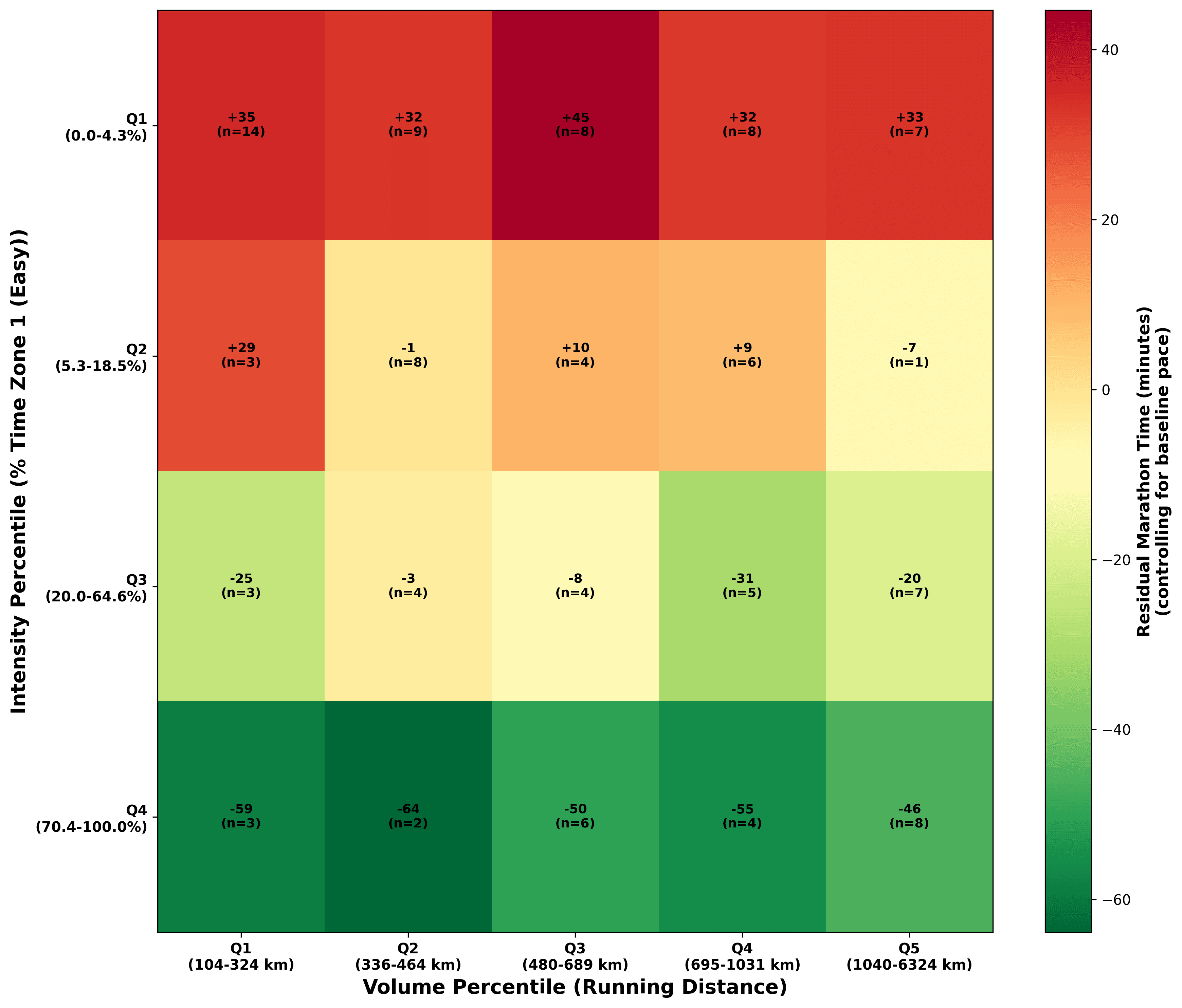

Figure 3 demonstrates the idea that aerobic/easy volume is the primary driver of marathon success beyond baseline level, and that skimping on easy running is one of the most reliable ways to leave huge potential on the table. In practical terms, it visually confirms why elite and high-performing recreational marathoners gravitate toward 65–85% easy training: the curve rewards aerobic dominance far more than balanced or intensity-heavy approaches.

The most striking pattern in Figure 3 is the near-uniform deep green across the entire bottom row (Q4: 70–100% easy), regardless of whether volume is low or extremely high, meaning runners who make easy/aerobic training the overwhelming majority of their workload consistently outperform their baseline by 46–64 minutes on average.

In sharp contrast, the top row (Q1: 0–4.3% easy) is almost entirely deep red (+32 to +45 min residuals), showing that very low easy proportions lead to severe under-performance even among high-mileage athletes (look at the top-right cells). Within each fixed volume level (each column), moving upward toward higher easy percentages yields large, consistent gains from red to green. Volume itself adds the most benefit precisely when easy training already dominates; without that easy foundation, adding more kilometers often yields little improvement or even worsens outcomes.

Importantly, the intensity distribution effect seen here is not just about volume; it holds across the entire volume spectrum, meaning that prioritising a very high easy percentage delivers outsized advantages even for lower-volume runners, while very low easy percentages produce disappointing results even for those logging extremely high mileage.

This reinforces how runners allocate effort (especially the dominance of easy aerobic work) is more determinative of marathon success than sheer quantity of kilometers alone.

Training For Your Next Marathon

This is all very interesting, but at Terra Research, we aim to build products that help people live healthier lives and perform better. In the last blog, we built a marathon prediction model that predicted marathon performance relatively inaccurately. Can we do better with more advanced techniques?

We changed our approach here to use the number of runs per week as the base. This is because frequency reflects real-life constraints—recovery windows, work schedules, family time, injury risk—and it strongly shapes how intensity should be distributed for optimal results. First, we looked at the intensity distributions that led to the best performance at each frequency level. You can see this in the table below.

| Runs/Week | Zone 1 (Easy) | Zone 2 (Moderate) | Zone 3 (Fast) | Total Volume | Avg Run Length | Marathon Time | Potential Improvement |

| <1 | 19.3% | 28.1% | 52.7% | 151 km | 15.7 km | 239.9 min | 61.5 min |

| 1-2 | 31.2% | 45.2% | 23.6% | 365 km | 12.7 km | 215.7 min | 53.2 min |

| 2-3 | 40.8% | 38.7% | 20.5% | 480 km | 11.7 km | 210.6 min | 46.6 min |

| 3-4 | 63.5% | 30.0% | 6.4% | 641 km | 11.9 km | 187.4 min | 48.0 min |

| 4-5 | 76.2% | 20.7% | 3.1% | 921 km | 11.3 km | 192.5 min | 50.1 min |

| 5-7 | 75.2% | 20.7% | 4.2% | 702 km | 11.6 km | 176.5 min | 60.6 min |

| 7+ | 88.0% | 9.0% | 3.0% | 2,345 km | 11.8 km | 174.9 min | 53.2 min |

The table shows a clear pattern: at low frequency (1–2 runs/week), training needs balance. That means higher proportions of moderate and fast with longer average runs in order to extract maximum benefit from limited sessions. As frequency rises (3+ runs/week), the pattern shifts dramatically toward extreme easy dominance (63–88% Zone 1), with fast work dropping to just 3–6% and moderate receding. Volume scales with frequency, but average run length stabilizes around 11–12 km beyond 2–3 sessions, emphasizing consistency over forcing ultra-long efforts.

The Model

After extensive work and experimentation, we identified a model approach that delivers slightly more accurate predictions than its linear counterpart. Achieving an impressive R² of 0.7933, it explains nearly 80% of the variance in marathon finish times, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of just 18.32 minutes and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 13.83 minutes.

At its core is an equation that starts with an intercept of 41.77 minutes and adds a dominant baseline pace term (+30.58 min per min/km slower pace), then layers in piecewise volume effects (minimal impact below 523 km, small but meaningful gains above), a square-root transformation for Zone 1 easy percentage (capturing accelerating aerobic benefits), piecewise fast training penalties (beneficial below 20%, harmful above), runs per week, and four critical standardized interactions that reveal how volume amplifies easy training's advantages while magnifying fast training's risks, and how faster baseline runners extract disproportionately large gains from both volume and easy work.

What makes this model particularly powerful is its ability to reflect physiological reality rather than average trends. Baseline pace remains the strongest single driver, but training effects are far from linear: easy running delivers compounding returns as its share rises (e.g., jumping from 40% to 60% easy can save ~7.2 minutes more than earlier increments), fast work flips from slightly helpful to clearly detrimental above 20% (adding 10% fast beyond that threshold costs ~5.3 minutes), and volume shows classic diminishing returns with a breakpoint at ~523 km.

These interactions add crucial personalization, faster runners benefit more from piling on mileage or easy miles, while slower runners see smaller (but still positive) effects, ensuring the model adapts to individual ability. In practice, this equation enables precise "what-if" simulations: enter your current baseline pace, volume, zone splits, and weekly runs, and instantly see the predicted time, plus how shifting 10% from fast to easy or adding one recovery run might shave minutes off race day.

By encoding the non-linear truths of endurance physiology, this model doesn't just describe what works on average; it predicts what could work best for you. Whether you're a time-crunched runner juggling 3 sessions a week, a high-frequency enthusiast stacking 7+ runs, or someone rebuilding after injury, the equation adapts, revealing precise trade-offs and upside potential in real numbers.

At Terra Research, this is the kind of insight we build toward: data that doesn't dictate, but hopefully illuminates a clearer, healthier, faster path. Next week we’re excited to launch a marathon pace calculator based on this model, so you can plug in your baseline pace along with how often you run, how much you run, and how hard you train, and get a realistic estimate of race day pace.